The donkey was a very useful animal in the bog. He was lighter than a horse and easier fed. If the bog was fairly firm a donkey and cart could be used to put out turf. The cleeves were used in th, softer bog. They were large baskets and some opened at the bottom to empty the turf. How- ever, for transporting the turf from the bog the horse and cart was more useful.

Cutting the turf was a man's work, but the whole family took a hand in the harvesting. The turf was cut with a slean, a tool resembling a garden spade with a wing on one side of the blade. The bank was scrawed first. The top sod, which was not used for fuel was removed. Then the cutter dug into the soft peat with the slean and threw huge sods onto the bank. Some preferred to cut breast turf. They plunged the slean horizontally into the bank at breast level. Each depth of a sod was called a 'spit', and the cut-away section of bog was called the 'log fuff" or "log spit."

As the sods were thrown onto the bank they were spread to dry in the sun and the wind. By the time the turf was ready for use it might have shrunk to less than half its original size. When the sods were firm enough to handle it was footed. Ten or twelve sods were stood on end in a cluster so that the breeze could pass through and dry them. The next stage was the re-footing. The footings were dismantled and any turf not completely dry was built in a loose heap called a clamp, while really wet sods were built into a larger footing. These jobs involved a great amount of stooping so there were more suited to children.

Our bog was in Doogra, a few miles beyond Newport. In the early days mammy sometimes accompanied daddy to 'the bog. They would walk there and back. They passed by a house owned by Tailor Mulchrone. Mrs. Mulchrone was a friendly woman and she would stand at the gate to pass the time of day with people going to the bog. Mammy liked the lady, but she often complained that she would spend the whole day talking. It was not that mammy did not like talking, but there was so much time spent travelling that any time remaining was precious. Mammy also maintained that people on neighbouring banks did not like to see daddy coming because there would be very little work done. He would waste the time talking and telling yarns.

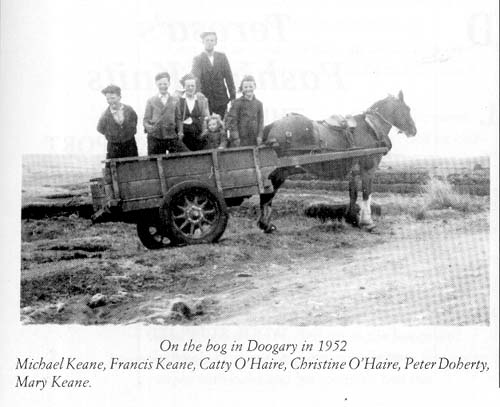

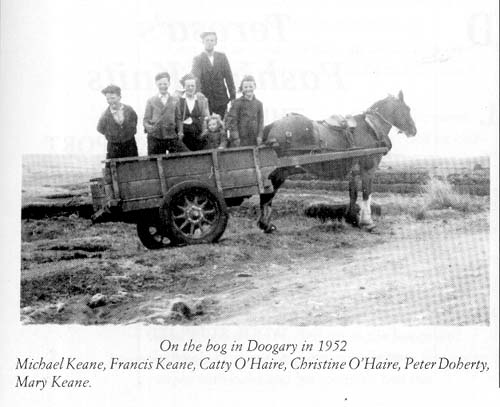

As soon as we were old enough we took our turns at going to the bog. We travelled by horse and cart. We looked on it as an outing. Mammy remained behind to mind the farm and the rest of us piled into the cart. As we passed by O'Malley's the horse smelled pigs. He refused to pass at first and daddy had to take hold of the bridle and lead him past the sty. As we went down the steep hill at George's Street in Newport, we got out to walk for fear the horse might slip on the smooth surface of the road.

We stopped to get spring water at Horan's well. By this time we had turned off the main road to take a byroad. The closer we got to our bog the more the road deteriorated. By the time we found our bank the road was nothing more than a track, paved with gravel, heather and bushes to prevent sinking.

The horse was unharnessed and allowed to graze while we set to work. We had brought with us food enough for two meals, as the bog is a hungry place. At noon we heard the Angelus bell ringing in Newport Church. This was the signal for tea. Daddy got the fire started. A black battered old kettle was filled and placed to boil. Sometimes we might have eggs with us.

These we would boil in the kettle. If there were no old kettles available a tin can sufficed. Once a kettle was used in the bog it was virtually impossible to remove the black stains. The bottle of milk was retrieved from the stream where it had been left in order that it would not go sour. Sandwiches of home baked bread, spread with country butter and filled with cheese or cooked meat, were the normal fare.

While the tea was being prepared some of us would wander too far or stray into soft ground. Jim and I usually looked after the horse whole Julia got the tea. When the tea was ready we found a sheltered spot and spread coats and sat to eat. The tea had distinctive tang, slightly smokey and pleasantly strong. It was better than a picnic. Perhaps it was the bog air that gave everything the extra flavour.

When he had eaten, daddy went to visit men working on the adjoining banks while we packed the remaining food for the evening meal.

One day as I bent to pick up the coats a clod of turf whistled past my ear and I heard a voice say: "Red heads are game an' black are the same. Mike Heshtin will have to get a good dog or buy a shot gun."

Embarrassed, I ran to help Julia to tidy the tea things away and peeped furtively from behind the turf stack at the man who had come from the direction of the lake. I would have taken him for an old-age pensioner were he not so nimble on his feet. He wore a shirt open to me waist and with the sleeves rolled up to his elbows. His tweed trousers was rolled up to the knees and tied with a piece of tight rope. His bare feet were purple with cold and his toe nails had the appearance of not having been cut for perhaps a year. His jacket was slung over his shoulder and he wore a cloth cap. His moustache was tobacco stained and he was chewing and spitting.

His opening remarks were for daddy's benefit, but daddy was too far away, and too engrossed in conversation to have heard. A group of men who were finishing an after lunch smoke across the road rose when they heard the voice.

"Good evenin' John. Did ya get up before the brikfisht?" called David Horan.

"Ya scoundrel ya.l'm not talkin' to you. You hid me torch last night, I could've gone into a bog-hole," shouted John.

"Sure you'd have a great funeral. Did ya hear Mac had turf taken on 'him?", queried David.

"What are ya lookin' at me for? Ya know where I was lash night. The divil shoot that fella anyways, why doesn't he shtack it nearer the house. Nexht thing the guards 'ill be round the place," said John angrily.

They continued the conversation as they moved out of earshot down the bank to where daddy and some other men were chatting.

"That's John Walsh for ye now," said daddy when he returned to resume work. It was the first time I had seen John in the flesh though I had heard many tales about how the lads in the bog and his neighbours liked to knock a rise out of him. He lived with a sister and it was rumoured that at night he went out and took a bag of turf here and there from various stacks. He detested the guards and the courts. I never saw him wear shoes. He would require a pedicure first. He always looked cold, yet he never wore his jacket, just slung it over his shoulder.

The six o'clock Angelus bell rang out in the clear air. At this signal we sat to eat the remainder of the food. This time we made sure the fire was quenched when we tidied up. We filled a few sacks of turf and put them in the cart for bringing home. Then, back to work for another couple of hours before finishing for the day. Jim and I went to fetch the horse. Jim led him back by the bridle while I went ahead to find solid ground or stones on which to walk the horse. As I did so I recalled how, years earlier, I walked ahead of Jim in the long grass. He was then afraid of snails and I walked ahead to make sure there were none in his path. Now I was in front of him again.